In the course of getting ready to move, I've been downsizing by culling and recycling my accumulated reprints, which were stored in 11 full, letter-sized file cabinet drawers. [Who said that? There's nothing wrong with being anal retentive!] Making the tough decision about what to leave in and what to leave out of my collection was fairly straightforward---I'm keeping only the articles published in books or obscure periodicals. That's because, as a retiree of the University of California I will have library privileges until I croak [including remote access via the web]. So, it'll be easy to acquire electronic versions of [nearly] anything published in referred journals. 'Kay so, one that I came across and am keeping is Robin Ridington's 1982 Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology paper, "Technology, World View and Adaptive Strategy in a Northern Hunting Society." That article and several of Ridington's others point up a distinction not always uppermost in the mind of archaeologists. Where 'technology' is concerned, the 'nology' comes first.

Archaeologists are almost obsessive when it comes to what they universally identify as "technology," or [the almost anachronistic] "material culture." I don't know about you. But, when I'm thinking about where my next meal is coming from, I only have to decide between the technology of the stadium-sized supermarket and that of the local greengrocer. It's not hard to keep those choices in mind. First, I make a list, then I get in the car, and a-shopping I do go. The automobile technology makes the trip faster, which means that upon my return I'll have time left to cook dinner before it's time for bed. Cooking with gas technology removes the need to obtain fuel beforehand, saving more time and letting me watch an episode or two of Doctor Who before beddie-byes. And so on.

|

| Hand-held GPSs |

|

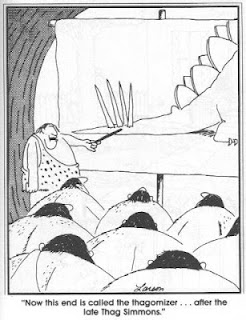

| With thanks to you-know-who, the artist, who, unbeknownst to him is supporting the SA's efforts, despite intellectual property niceties. For the sake of laying the blame, here's the URL this cartoon came from. |

Perhaps it's only me who thinks this way. I'll let you be the judge. If you've ever been tempted to think of Ancient Rome on the one hand and ancient northern Russia on the other, with the idea in mind to figger out why one historical trajectory was so much unlike the other. Whether or not you succumb to the temptation now and then, or are perfectly reflexive and never mistake the "thing" for the mental faculties that brought it into being, you might still want to read on. 'Cause there's one beauty of a photo, and a pretty cool description of a road trip that you might find interesting or thought-provoking.

So, let's first contrast my heavily technology-dependent shopping trips with the likes of this

When the grass stalks die and turn a reddish colour as the dry season approaches, it’s time to look for prawns in creeks. When the grass seeds turn brown and start falling, the dry season has started and it’s time to fish for barramundi. When the grass has burnt, the turtles are fat and ideal to hunt. (Muller, Natalie. "Mapping Aboriginal knowledge of the bush," Australian Geographic, December 26, 2012.)

|

| Molly Yawulminy hunts for long-necked turtle in the Daly River, NT. (Credit: Australian Geographic's Marcus Finn) |

|

| The Simpson Desert |

The distance from our camp at Yunala was 43 km [about 30 miles], all cross-country; the mean direction was west-south-west, with a detour to dig for kante (stone knives). The courses and distances were as follows:1. A little south of west 7 km to Namurunya soak—a tiny hollow that seemed, to my eyes, to have no identifying marks.The Pintupi's route finding by the unremarkable topographical features that were landmarks for these several important places was uncannily accurate. They always knew just where they were, they knew the directions of ecologically and spiritually significant places over a wide area and were orientated in 'compass' terms. (Lewis, David, "Route Finding by Desert Aborigines in Australia," Journal of Navigation 29(01):21--38, 1976.)

2. South-west 13 km to the kante site near a low and inconspicuous rise called Yirumora hill.

3. South-east 5 km, then back round the end of a tali (sandhill), to Rungkaratjunku sacred site.

4. Winding in and out between tali, generally west-south-west 16 km to Tjulyurnya rock hole by a low hill.

The sacred place was 2 km beyond.

Lewis is careful to point out that, no matter where they were, his guides were accurate to within about 10° when estimating the four cardinal directions and their subdivisions. More incredible, still was Lewis's description a round-trip of some 1600 km [that's about 1000 miles!] through the [to him and to most of us] "trackless" and "featureless" desert. The Simpson Desert [yes, yes, just a portion of it] is pictured below. Remember, too, that the trip was undertaken with only the "map" in the minds of the aboriginal people who guided him. And, by the way, that's navigation without using the stars! Many, many people of European descent are rightfully in awe of the knowledge required for such journeys. You can say all you want about dry grass and turtles, but you can't deny that the "technology" Lewis's guides were using was infinitely more accurate and precise than any hand-held GPS. How can I say that? Hmmm. Let's see... Oh, yeah. They've been doing it for around 40,000 years. No GPS. No lithium batteries. No compass. No surveying instruments. I think it's safe to say that all of the technology that goes into making a GPS couldn't hold a candle to the Aboriginal mind. More importantly, you'd have a far better chance of learning how to make and use a GPS than you would if you were trying to learn to navigate the Simpson Desert sans compass. Just sayin'.

|

| The Simpson Desert. To whomever put this up, thanks for the loan of this photo. This is the caption, if anybody cares to translate! Этот неприветливый образец природы признан национальным парком и постоянно влечет туристов. Но пустыня Симпсон к неопытным путешественникам беспощадна: она изматывает жарой, выпаривает жидкость в моторах, не дает вернуться. Температура в пустыне летом может подниматься до 50 градусов. После нескольких трагических случаев правительство Австралии закрыло Симпсон для посетителей на летний, особенно жаркий, период. Here is the URL. |

In remembering Ridington's work, I've used as an example one of the least materially complex cultures on Earth. Yet to me, navigating unerringly the breadth and depth of the Simpson Desert with nothing but one's eyes and memories makes Aboriginal knowledge the Eighth Wonder of the World---ancient and modern.

What I've written today is not intended to point fingers at archaeologists [even subversive ones]. It's merely a reminder that there's no more relevant a "technology" than the one betwixt our ears.

* Thog [legendary mammoth hunter], son of Thig, son of Thug, son of Thag [legendary stegosaurus hunter].

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for visiting!

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.